Tarantula spider facts

Vulnerable spiders?

Despite being a predatory animal, the spider can also be predated upon. With tarantulas, their major predator is a large member of the wasp family Pompilidae. The larger of these wasps are known as “tarantula hawks”. They will track down a tarantula using their sense of smell and paralize it dragging it back to its burrow. The wasp then lays an egg on the hapless tarantula’s abdomen then seals the spider in its burrow and goes off to find more prey. The wasp larva then hatches and feeds on the spider. Another known predator of

tarantulas are giant centipedes, particularly Scolopendra gigantea. This species is known to be a very aggressive carnivore that will attack and eat almost anything it comes across including tarantulas. In some parts of the Americas, tarantulas are classed as a delicacy. They are quite often roasted over an open fire to remove the hair before being consumed.

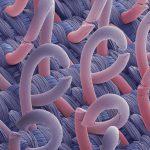

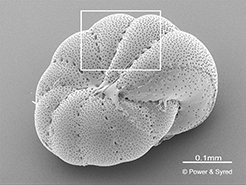

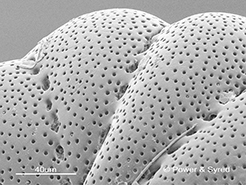

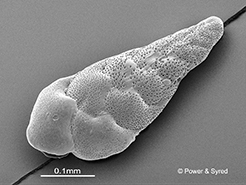

Urticating hairs of the Brachypelma smithi tarantula

Some of the “new world” tarantulas have two major defence systems, the obvious being venom but also they have special hairs on their opisthosoma or abdomen known as urticating hairs. When in fear of attack, they will rub their hind legs against their abdomen flicking these urticating hairs at the enemy. The tiny hairs or bristles get into the skin and mucous membranes of the attacker and can cause much irritation and even edema which is sometimes fatal. Studies on these special bristles indicate that they cause both mechanical and chemical harm to the membranes and skin. After kicking off the hairs, the tarantula will have a bald patch on its opisthosoma. The hairs will not grow back but will be replaced when the spider next moults.